Legacy Part 2: Country Dick Montana and the Snuggle Bunnies at the Spring Valley Inn every weekend forever

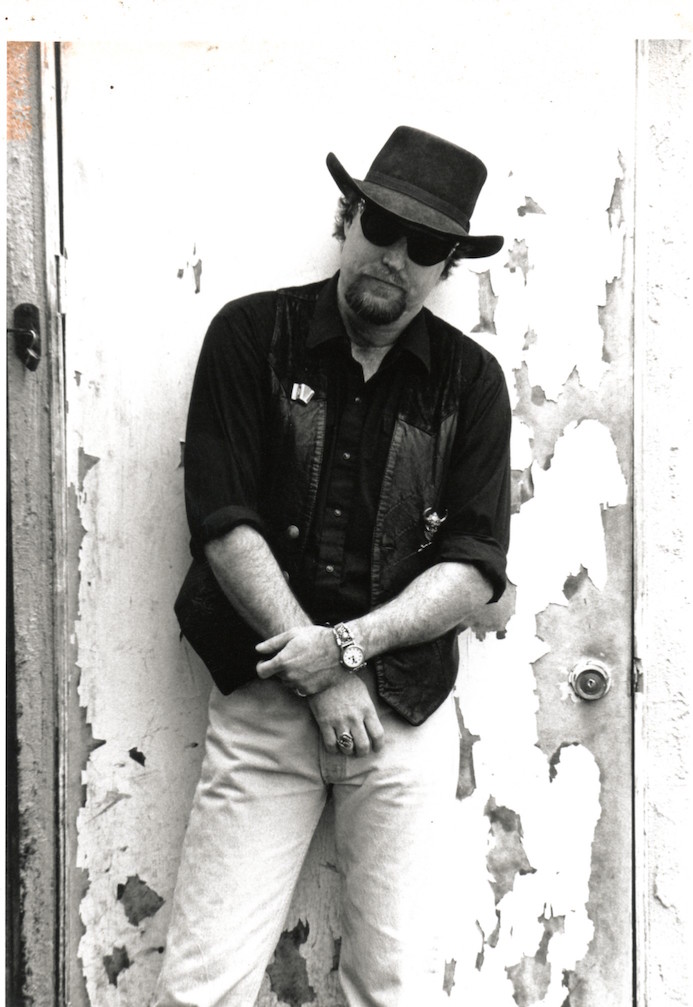

Editor’s note: This is the second of a series of articles about Country Dick Montana, who died onstage in Whistler, B.C., 20 years ago, Nov. 8, 1995.

It was a surprise to his friends when Dan McLain, a lover of punk rock and president of the Kinks Preservation Society, turned country.

McLain, who was in his mid-20s, took his friend since childhood, Joel Kmak, aside at a party and said he was now answering to the name Country Dick Montana.

“I’m in the kitchen and he’s out in the living room and he’s wearing a cowboy hat and cowboy boots,” Kmak said. “We know the Stray Cats are getting big, but what the fuck? What’s this country shit? We all like Gene Vincent. Why don’t you go the Gene Vincent route?

“We’re all kind of scratching our heads. People were like, ‘He’s fucking crazy.’ Hey, Dan’s a good friend and if he wants to be called Country Dick, who am I to say? So sure, I’ll call him Country Dick.”

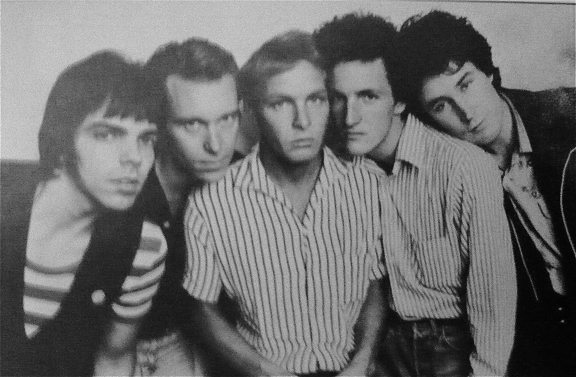

McLain and Kmak had been playing musical chairs at the drum kit for a punk rock band called the Penetrators. Kmak was the original drummer, but he moved to San Francisco to join another group, the Hitmakers. McLain had played with the Crawdaddys, which had an album and a couple of singles. The Penatrators band was a step up, to be sure.

Dan Perloff, who enrolled at San Diego State University in 1979, was heavy into the city’s music scene. “The Penetrators were by far the biggest band in San Diego,” said Perloff, who four years later would sign the Beat Farmers to the music label Rhino Records.

McLain was too much of a showman to be content to merely play drums, so he left the Penetrators to start his own band. That’s when Kmak returned to the Penetrators and McLain transformed himself to the Country Dick Montana persona, both on and off the stage.

“He asked for all of my country records, but I didn’t really have that many,” Kmak said. “At that time, we weren’t really big country fans. He thought the Everly Brothers were country, so he took them. He took a Johnny Cash. He even took my wife’s Linda Ronstadt records, the Stone Poneys. I didn’t realize it at the time but he was doing his homework for (his next band) and subsequently the Beat Farmers.”

McLain was inspired by Rank and File, the pioneering cowpunk band with Alejandro Escovedo and brothers Chip and Tony Kinman, formerly of the Dils. The music was an amalgamation of visceral punk rock presented in country and western fashion.

He attempted to start a band called the Country Dicks. That band would have included Nino Del Pesco, Robin Jackson and James Krieger, aka Jimmy Puppie from the Puppies. But after just one rehearsal, Krieger dropped out.

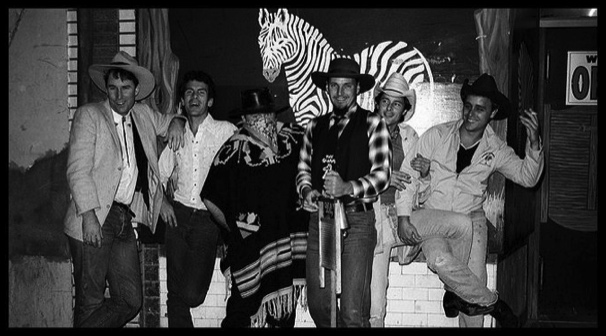

With encouragement from Pesco, he then formed Country Dick and the Snuggle Bunnies.

Seeking players, Country Dick went to a band from Coronado called the Fingers, which featured guitarists Joey Harris, Paul Kamanski and Billy Thompson. Well known throughout the region, Thompson went on to have a successful career in blues, playing with Albert King, Earl King and Little Milton and so far has released seven solo albums.

Country Dick was enthused about Thompson, but it was Harris and Kamanski who showed up for an audition.

“Dick had a house under a power transformer,” Kamanski said. “When you went there, it felt like you were getting cancer. There were a bunch of musicians living there and they didn’t have pots or pans. They just cooked weenies on top of a burner. You walk in the place and go, ‘Fuck, I know I’m going to walk out of here with crabs.’ ”

Country Dick initially was disappointed Kamanski had shown up, and not Thompson.

“I’m supposed to be this marvelous player,” Kamanski said, “so Dick says, ‘What the fuck, I thought he was good,’ because Dick thought I was supposed to be Billy Thompson. I was just learning.”

The meeting, however, was most fortuitous. Kamanski is a brilliant songwriter who contributed to every Beat Farmer record, even playing on the last one. Harris, of course, wound up in the Beat Farmers. Kamanski and Harris joined the Snuggle Bunnies as Country Dick’s version of the harmonious Everly Brothers.

“When Dan had met Paul and Joey, I was kind of butt hurt,” Kmak said, “because he’s got all these new friends from fucking Coronado, the rich side of town. What the fuck? And now all of a sudden he wants to be called Country Dick. Some of his old friends were kind of taken aback. I was even kind of taken aback.”

Country Dick was amused by Harris and Kamanski, who had been buddies since high school.

“He thought we were so weird because we drank the same water as the Doors because Jim Morrison was from Coronado,” Kamanski said. “He would always say that. We’d say, ‘We’re not drinking any water, Dick. We’re always drinking alcohol.’ ”

Joey Harris described the Snuggle Bunnies as Country Dick’s testing lab for an alternative country rock band.

Country Dick Montana liked to discover and collect music and he developed a penchant for doing the same thing with musicians. The Snuggle Bunnies included Del Pesco on bass; Skid Roper on guitar, mandolin and washboard, and Jackson on guitar and vocals.

“(Jackson) was a crusty old wonderful guy who sang all the George Jones songs,” Harris said. “The Spring Valley Inn was where Country Dick and the Snuggle Bunnies held court every Sunday. We used to play from 2 in the afternoon until closing and it was just a drunken fuckfest. It was just amazing. We had the best time.”

While playing pool with Spring Valley Inn’s Edwin Nutting, Del Pesco negotiated the Snuggle Bunnies residency as the house band. The Bunnies were paid a pittance, but they had an open bar tab.

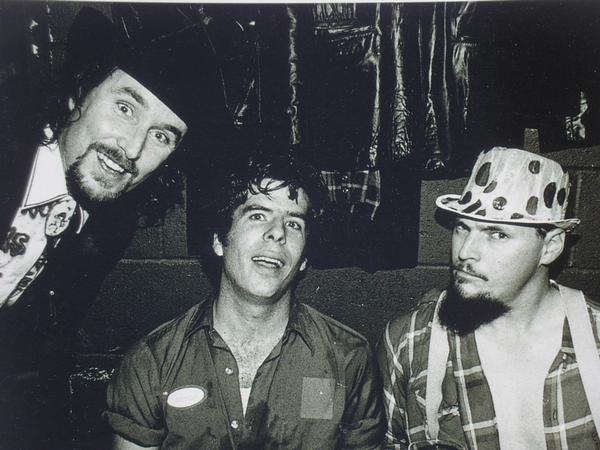

About that time a frenzied, foul-mouthed and quick-witted musician from Virginia made the scene: Mojo Nixon, who, like Montana, used a pseudonym.

“When I first moved to town, I saw the Penetrators,” Nixon said. “And shortly thereafter, the Snuggle Bunnies used to play every Sunday night at the Spring Valley Inn, and I became a regular and I was their biggest fan. I got to know Country Dick, and I was briefly in the Crawdaddys, which he had been in. A lot of people had the same idea, simultaneously, we’re going to take the Clash and the Sex Pistols and we’re going to combine it with Johnny Cash and Chuck Berry. He had that same idea, like a lot of people did.”

County Dick had a penchant for rewriting the lyrics to country standards such as Kenny Rogers’ “Lucille” and Eddie Arnold’s “Cattle Call,” which he changed to “Bunny Call.”

“It was about a wild guy on a horse riding out on the Plains,” Kamanski said. “He would sing with this high register that sounded like Aunt Bee on crack. You’d go, ‘Oh my God, that’s disturbing.’ Skid Roper (aka Richard Banke), a Snuggle Bunny, introduced us to that song. He would change the words to songs from ‘His heart was a feather to a hard on in leather.’

“The funniest thing was when the old folks would show up to the gigs who remembered the originals, and they would hear the blasphemy. You know that old-lady look when a two-stroke motorcycle goes by when they’re walking their dog and they get that downturned lip look. He would just insult them and they’d start smiling.

“I remember one time a guy was heckling us at the Spring Valley Inn,” Kamanski said. “Joey and I, and Dick’s a pretty tall guy and you put that duster on him. The guy kept kind of insinuating that we were kind of gay. After he did that about four or five times, Dick had just had it. All I remember is this white shadow just fly past the microphone. He jumped off the stage and beat the shit out of this guy. And then got back up onstage and started playing the next song like nothing had happened. I just went, ‘He’s my fucking hero.’ ”

Country Dick’s relentless energy that friends described from the high school days, only increased as an adult.

“He would just make us work,” Kamanski said. “We were learning songs in the parking lot a half-hour before you go onstage and he would do that every fricking night. I’d say, ‘Dick, we’ve got 90 songs,’ and he’d look at you and go, ‘What’s wrong with another 90?’

“ ‘You’re playing drums. You don’t have to memorize all these lyrics,’ Montana’s bandmates would say, “and he’d look at you like you were an idiot. (He would say:) ‘No this is your job. You have to learn all these songs.’

“We’d be in the parking lot learning an Everly Brothers song and then go into the bar and play the damn thing. We’d start at 6 and rehearse until 9 and then stay in the bar until closing time. We would sit there at the Spring Valley Inn and play Wednesday through Sunday for a whole year with no breaks and every night write another song in the parking lot and play it six or seven times in front of the same drunks at the end of the bar. But by the end of the year, that bar had a line down the street and it was sold out.

“To me, it was too wacky and I wanted to do something else and Joey wanted to do something else. There was nothing wrong with it. There was no reason for it to end. I think Dick was looking at how he could make it evolve.

“We were doing a lot of original songs but also a lot of covers, stuff you would hear in any bar in California that people would consider kind of country music. But we were just rocking it up. We would take Hank Williams songs and play the shit out of them really fast with lots of guitar solos and a lot of buffoonery. But I was always thinking, ‘Can I have a more serious type of group? We had played every bar in town. How far can we go?’

“He took that vehicle but with completely new players and took that formula with original music and upped the game. He turned it into the Beat Farmers.”

Go to Part 3

Editor’s note: This is the second of a series of articles about Country Dick Montana, who died onstage in Whistler, B.C., 20 years ago, Nov. 8, 1995.

It was a surprise to his friends when Dan McLain, a lover of punk rock and president of the Kinks Preservation Society, turned country.

McLain, who was in his mid-20s, took his friend since childhood, Joel Kmak, aside at a party and said he was now answering to the name Country Dick Montana.

“I’m in the kitchen and he’s out in the living room and he’s wearing a cowboy hat and cowboy boots,” Kmak said. “We know the Stray Cats are getting big, but what the fuck? What’s this country shit? We all like Gene Vincent. Why don’t you go the Gene Vincent route?

“We’re all kind of scratching our heads. People were like, ‘He’s fucking crazy.’ Hey, Dan’s a good friend and if he wants to be called Country Dick, who am I to say? So sure, I’ll call him Country Dick.”

McLain and Kmak had been playing musical chairs at the drum kit for a punk rock band called the Penetrators. Kmak was the original drummer, but he moved to San Francisco to join another group, the Hitmakers. McLain had played with the Crawdaddys, which had an album and a couple of singles. The Penatrators band was a step up, to be sure.

Dan Perloff, who enrolled at San Diego State University in 1979, was heavy into the city’s music scene. “The Penetrators were by far the biggest band in San Diego,” said Perloff, who four years later would sign the Beat Farmers to the music label Rhino Records.

McLain was too much of a showman to be content to merely play drums, so he left the Penetrators to start his own band. That’s when Kmak returned to the Penetrators and McLain transformed himself to the Country Dick Montana persona, both on and off the stage.

“He asked for all of my country records, but I didn’t really have that many,” Kmak said. “At that time, we weren’t really big country fans. He thought the Everly Brothers were country, so he took them. He took a Johnny Cash. He even took my wife’s Linda Ronstadt records, the Stone Poneys. I didn’t realize it at the time but he was doing his homework for (his next band) and subsequently the Beat Farmers.”

McLain was inspired by Rank and File, the pioneering cowpunk band with Alejandro Escovedo and brothers Chip and Tony Kinman, formerly of the Dils. The music was an amalgamation of visceral punk rock presented in country and western fashion.

He attempted to start a band called the Country Dicks. That band would have included Nino Del Pesco, Robin Jackson and James Krieger, aka Jimmy Puppie from the Puppies. But after just one rehearsal, Krieger dropped out.

With encouragement from Pesco, he then formed Country Dick and the Snuggle Bunnies.

Seeking players, Country Dick went to a band from Coronado called the Fingers, which featured guitarists Joey Harris, Paul Kamanski and Billy Thompson. Well known throughout the region, Thompson went on to have a successful career in blues, playing with Albert King, Earl King and Little Milton and so far has released seven solo albums.

Country Dick was enthused about Thompson, but it was Harris and Kamanski who showed up for an audition.

“Dick had a house under a power transformer,” Kamanski said. “When you went there, it felt like you were getting cancer. There were a bunch of musicians living there and they didn’t have pots or pans. They just cooked weenies on top of a burner. You walk in the place and go, ‘Fuck, I know I’m going to walk out of here with crabs.’ ”

Country Dick initially was disappointed Kamanski had shown up, and not Thompson.

“I’m supposed to be this marvelous player,” Kamanski said, “so Dick says, ‘What the fuck, I thought he was good,’ because Dick thought I was supposed to be Billy Thompson. I was just learning.”

The meeting, however, was most fortuitous. Kamanski is a brilliant songwriter who contributed to every Beat Farmer record, even playing on the last one. Harris, of course, wound up in the Beat Farmers. Kamanski and Harris joined the Snuggle Bunnies as Country Dick’s version of the harmonious Everly Brothers.

“When Dan had met Paul and Joey, I was kind of butt hurt,” Kmak said, “because he’s got all these new friends from fucking Coronado, the rich side of town. What the fuck? And now all of a sudden he wants to be called Country Dick. Some of his old friends were kind of taken aback. I was even kind of taken aback.”

Country Dick was amused by Harris and Kamanski, who had been buddies since high school.

“He thought we were so weird because we drank the same water as the Doors because Jim Morrison was from Coronado,” Kamanski said. “He would always say that. We’d say, ‘We’re not drinking any water, Dick. We’re always drinking alcohol.’ ”

Joey Harris described the Snuggle Bunnies as Country Dick’s testing lab for an alternative country rock band.

Country Dick Montana liked to discover and collect music and he developed a penchant for doing the same thing with musicians. The Snuggle Bunnies included Del Pesco on bass; Skid Roper on guitar, mandolin and washboard, and Jackson on guitar and vocals.

“(Jackson) was a crusty old wonderful guy who sang all the George Jones songs,” Harris said. “The Spring Valley Inn was where Country Dick and the Snuggle Bunnies held court every Sunday. We used to play from 2 in the afternoon until closing and it was just a drunken fuckfest. It was just amazing. We had the best time.”

While playing pool with Spring Valley Inn’s Edwin Nutting, Del Pesco negotiated the Snuggle Bunnies residency as the house band. The Bunnies were paid a pittance, but they had an open bar tab.

About that time a frenzied, foul-mouthed and quick-witted musician from Virginia made the scene: Mojo Nixon, who, like Montana, used a pseudonym.

“When I first moved to town, I saw the Penetrators,” Nixon said. “And shortly thereafter, the Snuggle Bunnies used to play every Sunday night at the Spring Valley Inn, and I became a regular and I was their biggest fan. I got to know Country Dick, and I was briefly in the Crawdaddys, which he had been in. A lot of people had the same idea, simultaneously, we’re going to take the Clash and the Sex Pistols and we’re going to combine it with Johnny Cash and Chuck Berry. He had that same idea, like a lot of people did.”

County Dick had a penchant for rewriting the lyrics to country standards such as Kenny Rogers’ “Lucille” and Eddie Arnold’s “Cattle Call,” which he changed to “Bunny Call.”

“It was about a wild guy on a horse riding out on the Plains,” Kamanski said. “He would sing with this high register that sounded like Aunt Bee on crack. You’d go, ‘Oh my God, that’s disturbing.’ Skid Roper (aka Richard Banke), a Snuggle Bunny, introduced us to that song. He would change the words to songs from ‘His heart was a feather to a hard on in leather.’

“The funniest thing was when the old folks would show up to the gigs who remembered the originals, and they would hear the blasphemy. You know that old-lady look when a two-stroke motorcycle goes by when they’re walking their dog and they get that downturned lip look. He would just insult them and they’d start smiling.

“I remember one time a guy was heckling us at the Spring Valley Inn,” Kamanski said. “Joey and I, and Dick’s a pretty tall guy and you put that duster on him. The guy kept kind of insinuating that we were kind of gay. After he did that about four or five times, Dick had just had it. All I remember is this white shadow just fly past the microphone. He jumped off the stage and beat the shit out of this guy. And then got back up onstage and started playing the next song like nothing had happened. I just went, ‘He’s my fucking hero.’ ”

Country Dick’s relentless energy that friends described from the high school days, only increased as an adult.

“He would just make us work,” Kamanski said. “We were learning songs in the parking lot a half-hour before you go onstage and he would do that every fricking night. I’d say, ‘Dick, we’ve got 90 songs,’ and he’d look at you and go, ‘What’s wrong with another 90?’

“ ‘You’re playing drums. You don’t have to memorize all these lyrics,’ Montana’s bandmates would say, “and he’d look at you like you were an idiot. (He would say:) ‘No this is your job. You have to learn all these songs.’

“We’d be in the parking lot learning an Everly Brothers song and then go into the bar and play the damn thing. We’d start at 6 and rehearse until 9 and then stay in the bar until closing time. We would sit there at the Spring Valley Inn and play Wednesday through Sunday for a whole year with no breaks and every night write another song in the parking lot and play it six or seven times in front of the same drunks at the end of the bar. But by the end of the year, that bar had a line down the street and it was sold out.

“To me, it was too wacky and I wanted to do something else and Joey wanted to do something else. There was nothing wrong with it. There was no reason for it to end. I think Dick was looking at how he could make it evolve.

“We were doing a lot of original songs but also a lot of covers, stuff you would hear in any bar in California that people would consider kind of country music. But we were just rocking it up. We would take Hank Williams songs and play the shit out of them really fast with lots of guitar solos and a lot of buffoonery. But I was always thinking, ‘Can I have a more serious type of group? We had played every bar in town. How far can we go?’

“He took that vehicle but with completely new players and took that formula with original music and upped the game. He turned it into the Beat Farmers.”

Go to Part 3